Movies

New Releases • A-D • E-H • I-P • Q-Z • Articles • Festivals • Interviews • Dark Knight • Indiana Jones • John Wick • MCU

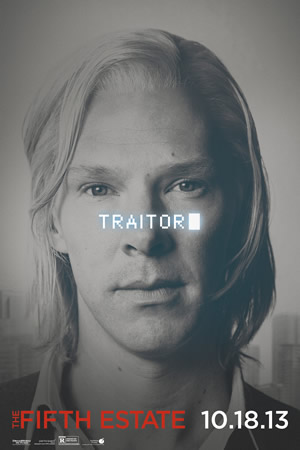

Daniel Domscheit-Berg (Daniel Bruhl) and Julian Assange (Benedict Cumberbatch) in a clickety-clack scene.

Photo: Touchstone Pictures/Dreamworks

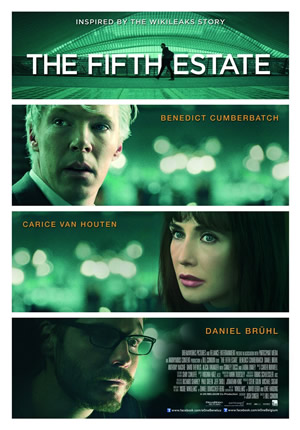

The Fifth Estate

Directed by Bill Condon

Rated R

Leaked 18 October 2013

The Fifth Estate is one of the year’s most exciting movies, but the excitement doesn’t stem from car chases, explosions or superheroes in colorful costumes. In this case the excitement is generated by the ideas on tap, the big picture issues addressed and the relevance to today’s instant-gratification, social-media driven world.

The Anti-Social Network

A few years ago David Fincher brought Mark Zuckerberg and the Facebook story to the big screen in The Social Network and it proved to be a not-so-engaging experience that didn’t collect very many “likes” at the box office. The story of a smug Ivy Leaguer making a mint off of other people’s private information isn’t great entertainment nor is it all that compelling.

Now director Bill Condon (Gods and Monsters) has brought Julian Assange and the WikiLeaks story to the silver screen and it’s a wholly different experience.

Zuckerberg and Assange have some things in common: both are widely considered to be egotistical assholes and neither gives a rat’s ass about other people’s private information. Both started Web sites that have made a significant historical, cultural and social impact.

But in terms of eye-opening narrative, Assange’s story trumps Zuckerberg’s in spades. Zuckerberg had it relatively easy. Assange put on airs of having an army of volunteers backing up his WikiLeaks project when in fact it was a one-man show and he struggled to support a single server and keep his site online; he was one guy with a couple fake email addresses and severe trust issues after having been betrayed by friends in the past.

Assange’s tale is much more fascinating and much more important. Sure, Facebook to one degree or another played a role in the Arab Spring, but Assange was on to something of even greater direct impact.

It’s unlikely The Fifth Estate will fare any better at the box office than The Social Network. Hopefully, though, it’ll earn enough respect to be a movie that comes up during conversations further on down the road, similar to All the President’s Men, which remains the standard-bearer for a cinematic account of investigative journalism. Journalism-based movies are a tough sell these days; The Company You Keep and State of Play are two other recent overlooked and excellent – albeit fictional – movies that deserve to be seen.

Sympathy for the Devil

The story plays out like something from a pulp thriller. The hero is also the villain and the stakes involve nothing less than world security. But that’s the sloppy end to an ambition that held so much promise for making a difference, for actually making the world a better place. Assange was able to shine a light into some of the world’s dark areas, at least in terms of political opacity and corruption. Human rights issues in Tibet and Kenya were exposed by a guy with self-professed humble beginnings. Who better to expose the world’s wrongs than somebody who had suffered his own injustices?

In Assange’s view, there are no secrets. None. Unless, of course, those secrets involve Assange himself. And that’s an angle The Fifth Estate deftly explores. Who is this guy with white hair? Assange himself has multiple explanations, all designed to elicit sympathy. At first he poignantly tells of his mother’s involvement in an Australian cult called The Family. After escaping from the cult, they were ruthlessly pursued and their lives were in danger. It was enough, Assange says, to turn his hair white. But, just like the Joker in The Dark Knight, who had multiple versions of how he got his facial scars, Assange has multiple accounts of how he got his white hair. And none of them reflect reality.

The initial fear was The Fifth Estate (the Fourth Estate being the free press) would lionize Assange as a folk hero, much as Eric Snowden’s recent exposure of American national security secrets garnered a coterie of fan support from those who viewed his actions as honorable. And don’t forget that part of this tale involved Bradley Manning, who recently reappeared in the news with his request to become a woman. He’s the guy who smuggled out hundreds of thousands of embarrassing private cables involving world leaders on a CD labeled as containing Lady Gaga tunes.

It takes reality to make a story that nutty and, ultimately, that episode would become Assange’s undoing.

To the credit of screenwriter Josh Singer (TV’s The West Wing), who based his screenplay on two books penned by Daniel Domscheit-Berg (Inside WikiLeaks: My Time with Julian Assange at the World’s Most Dangerous Website) and David Leigh and Luke Harding (WikiLeaks: Inside Julian Assange’s War on Secrecy), the story appears to give a balanced and rational account of the real events. Assange starts out as a sympathetic rebel in search of the ultimate expression of civil disobedience. Then, in a meltdown that borders on Shakespearean, Assange’s hubris is buoyed by financial support from key members of the media elite (The New York Times, The Guardian and Der Spiegel). No good can come from that Molotov cocktail.

Of course, Assange might have a thing or two to say to the contrary, but more on that in a bit.

Courage Is Contagious

Benedict Cumberbatch has already made a name for himself as an A-list actor with his terrific take on a modern-day Sherlock Holmes in the BBC series Sherlock, a small role in Steven Spielberg’s War Horse and an updated take on a classic villain in Star Trek Into Darkness. Here he takes things up a notch and the result is most certainly worthy of an Oscar nomination. Cumberbatch nails the mannerisms and voice inflections of Julian Assange. Add some makeup effects along with that famous hairdo and he’s an eerie visage of the real man.

Cumberbatch is accompanied by another terrific performance from Daniel Bruhl, who earlier in the month gave a masterful star turn as Niki Lauda in Rush. Here Bruhl portrays Daniel Domscheit-Berg (his significance was explained a couple paragraphs ago).

One of the most surprising elements of The Fifth Estate is its highly ambitious presentation of the material. This isn’t a story of a loner sitting in a dark room with the incessant clickety-clack of keystrokes. Sure, there is some of that, but there’s plenty of room for eye candy in this movie that takes full advantage of architectural elements in cities like Berlin and Liege, Brussels.

Cinematographer Tobias Schliessler (Dreamgirls), a fairly regular collaborator with director Condon, turns in his best work here with a stylish spin on what could otherwise be a dull necessity – people typing away on computer keyboards.

The tip-off that The Fifth Estate might actually turn out to be something more than a rote telling of recent history comes during the opening credits, which are set against scenes of typewriters, radios, celluloid, Morse code, newspapers – all those old-fangled ways of communicating news and alerting the masses.

Collateral Murder

There’s a perfect narrative arc at work here. From lionized in some circles (at one point comparisons to Mother Teresa and Nelson Mandela were bandied about) to demonized in others, the Assange story is remarkable on many levels. Breathtaking highs and soul-crushing lows dot the landscape, but Daniel’s girlfriend sums it up best when she describes Assange as a “manipulative asshole.”

Assange’s reticence to reveal his own truths only added fuel to the fire. The movie ends with him stuck in the Ecuadorian embassy in London amid allegations of sexual misconduct from women Assange at first claimed he never met. Then he admitted to knowing them but not the situation.

Assange wanted his privacy – and the privacy of those who supplied the leaks – the very thing he denied to so many other people because, in his view, to redact any documents, even for the sake of protecting innocent family members and children, was unacceptable. The process of editing documents injected bias into the material.

It’s a rather flabbergasting argument to make in such extreme cases as Assange quickly found himself mired. Perhaps when two of his friends were killed in Kenya there was a snap of reason, perhaps it was the last straw and it was time to be ever bolder.

Assange had a bold, brave idea – one the world really does need as a mechanism of global checks and balances. His cinematic doppelganger talks about how the world needs men of purpose; ideas are out there, but they need people of commitment to execute them.

All of those crazy events lead to an unexpected, eloquent conclusion to the movie played out as an interview at the embassy. It’s an exhortation from Assange for people to think for themselves. Assange bashes the two books which form the basis for this movie; it’s up to the viewers and readers to dig deeper into the facts and to keep pursuing the truth, he says. That’s where the power lies – in the truth – and that’s what puts the world’s leaders on edge.

Find the truth for yourself. Don’t accept at face value what the media doles out. Think for yourself.

Amid an increasingly lackadaisical population lulled into acquiescence via entitlements and freebies, a more timely and significant message is unimaginable.

• Originally published at MovieHabit.com.